July 5, 2018: A Djiboutian woman takes part in reheasals ahed of the ribbon cutting for the Djibouti International Free Trade Zone, a Chinese-backed venture in the Horn of Africa country.

YASUYOSHI CHIBA/GETTY IMAGES

In this Horn of Africa country, Beijing is helping to build an ultramodern trade hub – and, some fear, tighten its grip on Africa through multibillion-dollar loans. Can Djiboutians escape the debt trap?

Red-and-gold Chinese banners hang outside the headquarters of Djibouti’s free-trade zone, adding a splash of colour to the dusty desert gateway of this hugely ambitious project, the biggest of its kind in Africa.

Inside the building, Chinese businessman Robin Li stands over a scale model of the free-trade zone, telling a Ghanaian delegation that the Chinese investors will control just 40 per cent of the project. “We leave the money behind,” says Mr. Li, the vice-president of China Merchants Port. “No return!”

Everyone laughs uproariously, and then a local official tries to clarify the profits that could flow to the Chinese state-owned companies. “They don’t take big money,” he assures the Ghana delegation.

In fact, nobody quite knows what benefits Beijing will extract from Djibouti’s free-trade zone – a Chinese-financed project that could cost US$3.5-billion over the next 10 years, covering a vast 48 square kilometres.

But money is only one of the commodities in these transactions. Political influence and commercial power are the implicit commodities in China’s financial drive.

Countries across Africa and Asia are wrestling with the same dilemma as Djibouti: How to accept Chinese money without accepting Chinese control.

Beijing’s loans are accelerating the construction of the ports and railways that poorer countries desperately need. But the price could be steep: rising debts, a potential weakening of sovereignty and a possible loss of key assets if they default on their loans.

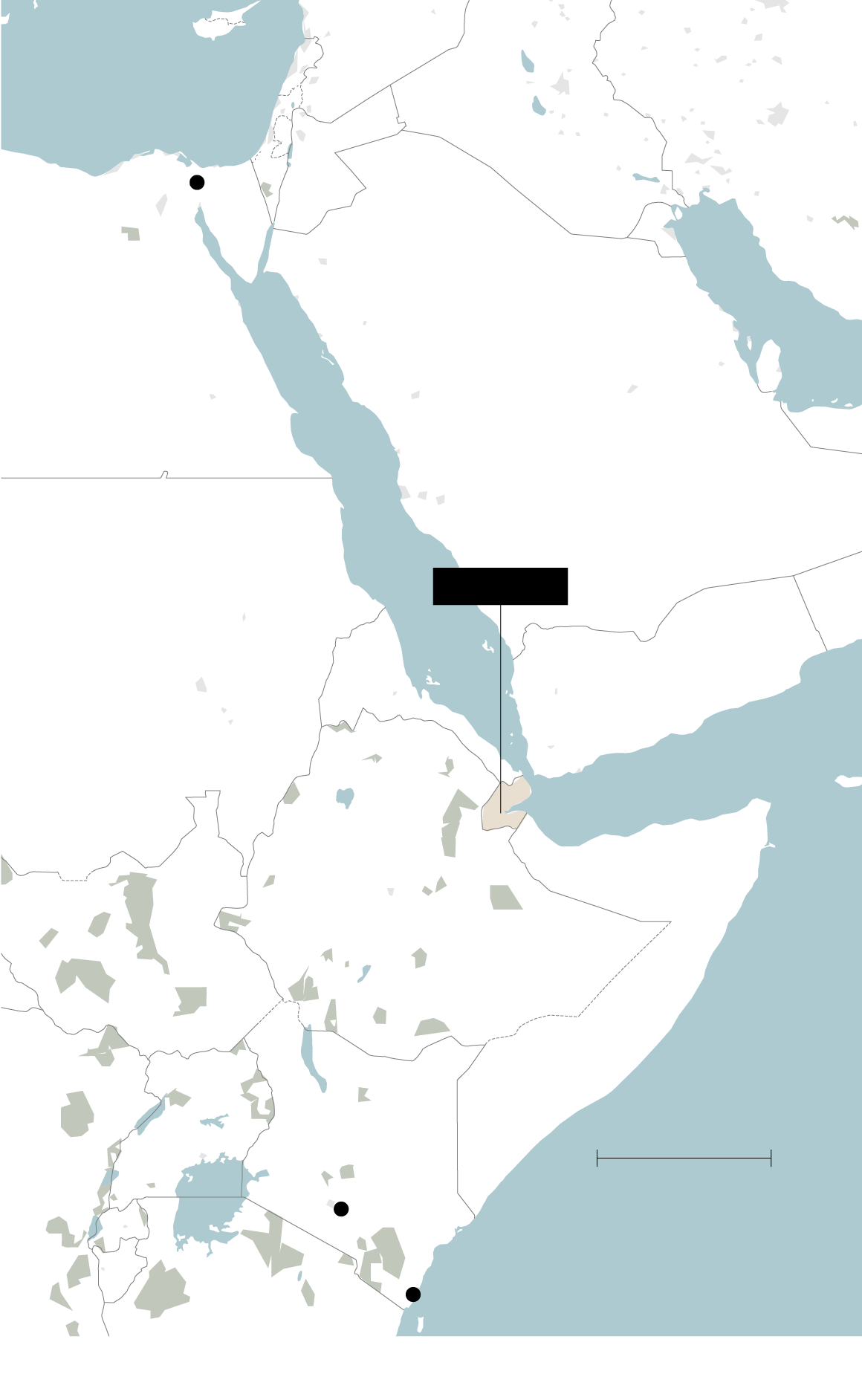

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: TILEZEN; OPENSTREETMAP CONTRIBUTORS; HIU

Djibouti is strategically located at the crossroads of Africa and the Middle East, on a narrow strait that controls access to the Red Sea and the Suez Canal. It has become a crucial hub in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI): a multitrillion-dollar plan to build modern infrastructure to connect at least 68 countries to Chinese trade routes.

John Bolton, national-security adviser to U.S. President Donald Trump, has alleged that the BRI is a predatory Chinese strategy, deliberately deploying “bribes, opaque agreements and the strategic use of debt” to hold African countries “captive to Beijing’s wishes.” The Trump administration has even produced YouTube videos attacking the BRI and urging countries to seek U.S. investment instead. “Don’t get caught in the debt trap,” the videos warn in ominous tones.

China has denied the debt-trap accusation, insisting that the loans benefit both sides. Some analysts say the allegation of predatory behaviour is exaggerated, since China has often ended up cancelling the debts of poorer countries, and a majority of the debt in most African countries is still held by non-Chinese lenders.

Djibouti, a tiny country of fewer than a million people on the Red Sea, is a prime example of the risks. It has enjoyed a booming economy in recent years, fuelled by huge Chinese loans and investment in ports, railways, warehouses, industrial parks and even a secretive military base. But critics have warned that the country is falling into a Chinese “debt trap,” in which the loans could overwhelm its economic independence.

The International Monetary Fund recently estimated that Djibouti’s public and publicly guaranteed debt has climbed to 104 per cent of its GDP – and the vast majority of this external debt is owed to Beijing. The Chinese loans have “resulted in debt distress, which poses significant risks,” the IMF said.

A separate study by the Center for Global Development, a Washington-based think tank, estimated that China has provided nearly US$1.4-billion for Djibouti’s major projects, leading to a sharp increase in the country’s external debt. Djibouti is one of eight countries worldwide where the rising debt from BRI projects is “of particular concern” because of the heightened risk of debt distress, the study concluded.

Djibouti’s Finance Minister, Ilyas Moussa Dawaleh, says the Chinese loans are crucial for preventing an eruption of protest among Djibouti’s poor and unemployed. “If we let the youths stay unemployed, tomorrow they will create instability, and some devil will come and make use of their frustration,” he told The Globe and Mail in an interview. “We thank the Chinese for our infrastructure development, and we want our other partners to help us – not just tell us about the Chinese debt trap. Maybe they think they are attacking China, but they are disrespecting Africans. We are mature enough to know exactly what we are doing for our country.”

Beijing has poured money into Djibouti in recent years. It gave a US$250-million loan for Djibouti’s free-trade zone. It provided about US$500-million in financing for the Djibouti portion of a new 756-km railway line between Djibouti and Ethiopia. And it lent a further US$400-million for a new container port in Djibouti.

In addition to the loans, Chinese state-owned companies have made equity investments in the Djibouti projects and have won management contracts in the ports and railway.

People hold Chinese and Djiboutian flags on July 4, 2018, as they wait for President Ismail Omar Guelleh’s arrival to launch a 1,000-unit housing project. The venture is supported by China Merchants.

YASUYOSHI CHIBA/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Djibouti has given China Merchants oversight of its Doraleh Multipurpose Port, which was financed and built by Chinese companies. The port makes Djibouti a key point in the multitrillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative to link China to markets in Africa, Europe and the rest of Asia.

GEOFFREY YORK/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

GATEWAY TO THE WORLD, TETHER TO CHINA

At the Doraleh Container Terminal, an ultramodern port on the edge of the capital, Djibouti cancelled a Dubai company’s contract to run the port, nationalized the terminal and then has reportedly allowed China Merchants to help operate it. (The government denies that China Merchants is the official operator of the port. The Dubai company has launched legal proceedings to challenge the takeover.)

In exchange for its loans and investments, China has gained crucial influence over the shipping lanes that flow past Djibouti to the Suez Canal – the same lanes that provide oil supplies for Chinese importers and vital routes to Europe for Chinese exporters. And if Djibouti is unable to repay the loans, China could end up with a bigger stake of the infrastructure.

Djibouti insists it is retaining a majority stake in each project. But when China finances the projects and holds a significant chunk of the equity, along with short-term contracts to manage and operate the railway and some of the ports, the Chinese influence can be massive.

“China is adept at converting development-minded investment dollars into geopolitical power and influence,” said a recent report by the Australian Centre on China in the World, based at the Australian National University.

“Djibouti’s future is now more tied to China than to any other partner,” it said.

Across the African continent, China has provided about US$130-billion in loans over the past two decades, and it promises a further US$60-billion over the next several years as its BRI strategy gains momentum.

But the exact terms of these loans are routinely kept secret. Africans often don’t know the repayment terms or the potential loss of collateral, including infrastructure or future resource revenue, if the loans aren’t repaid. Many of the benefits flow to China, since almost 90 per cent of BRI contractors are Chinese companies, which often hire Chinese workers rather than local workers.

“Countries rich in natural resources, like Angola, Zambia and the Republic of Congo, or with strategically important infrastructure, like ports or railways such as Kenya, are most vulnerable to the risk of losing control over important assets in negotiations with Chinese creditors,” said a report by Moody’s credit agency late last year.

Chinese loans to African countries have soared to more than US$10-billion annually in recent years, compared with less than US$1-billion in 2001. This is contributing to a growing crisis in Africa, where most countries are heavily indebted and some are unable to service their debts.

In Kenya, for example, the Chinese share of the national debt has been escalating rapidly. In total, Kenya owes more than US$5-billion to China today, a fivefold increase in just five years.

China persuaded the government of Kenya to build a costly new 485-km railway between Nairobi and the port city of Mombasa for about US$4-billion, rather than repairing an existing line for about a quarter of the cost. The project became one of the most expensive rail projects in Africa.

After opening in 2017, the railway lost US$100-million in its first year of operation, carrying far less freight than expected. The economic benefits to Kenya were limited, since Chinese contractors did most of the construction work. And the project left Kenya saddled with US$3.2-billion in debt to China. Kenyan media have reported that China could seize Kenyan assets, including the port of Mombasa, if the loan is not repaid. They also reported that the loan agreement requires any disputes to be arbitrated in China.

By 2019, the railway was continuing to lose money on each of its passenger and cargo trips, while Kenya’s loan repayments to China were sharply increasing. The government insisted that the loans weren’t harmful. “China is not seeking to colonize us, but they understand us and our point of need,” President Uhuru Kenyatta told local journalists.

The Kenyan railway – like the similar Chinese-funded railway between Djibouti and Ethiopia – has been a publicity bonanza for Beijing, creating highly visible Chinese branding on the trains.

The Kenyan railway is operated by a Chinese company, and Chinese workers have taken many of the top jobs as conductors, engineers, managers and drivers. In each train carriage, a Chinese flag is displayed. The stations are filled with Chinese signs and Chinese pamphlets, and the Mombasa station even features a bronze statue of a Chinese hero, the explorer Zheng He, who led a maritime expedition to East Africa in the 15th century.

In Djibouti, too, the new train terminal is filled with Chinese signs and banners, and most of the conductors are Chinese. Even the clocks on the wall are from China.

Chinese rail companies were hired to manage the US$4.5-billion Djibouti-Ethiopia electric railway for six years after its completion in 2017.

“Of course, if the investment is coming mainly from China, we will see sometimes Chinese signs and communications,” says Mr. Dawaleh, the Finance Minister. “We need to bring global talent.”

Others are more critical. “How can Djiboutians see this railway as their own if everything they see is Chinese?” asks Abdirahman Mohamed Ahmed, an economic and environmental consultant in Djibouti.

“China is doing the same as what we criticized the former colonialists for doing,” he told The Globe. “China should be more sensitive. They should be different from other empires.”

Ethiopia and Djibouti have both struggled with their heavy debts to Chinese financiers for the railway, and both have sought to renegotiate their loans. Late last year, China allowed Ethiopia to extend the loan repayment period from 10 years to 30 years.

The concerns over the railway loans are part of a growing international anxiety about China’s BRI strategy. Countries such as Sierra Leone, Pakistan and Malaysia have delayed or cancelled Chinese projects. Others such as the Maldives have sought to renegotiate or reduce their Chinese loans.

Many observers, including Africans, were alarmed by Sri Lanka’s loss of a Chinese-built port, Hambantota, after the South Asian country was unable to repay more than US$1-billion in debt to Chinese banks. Sri Lanka was obliged to hand over the port to China on a 99-year lease.

Djibouti officials, however, insist they aren’t at risk of suffering a similar fate. “We are always the majority shareholder,” said Aboubaker Omar Hadi, chairman of Djibouti’s ports and free-trade authority, who had made the comment about China not taking “big money.”

“The mistakes in Sri Lanka were made by the Chinese contractors, pushing for the contract and short-cutting the process to get the Chinese bank loan and leaving the debts behind,” he told The Globe.

“It was giving a bad name to China. The Chinese government was unhappy, so it disciplined those contractors. They’ve stopped these contractors from promising everything.”

Mail & Globe

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/CUXC5MTT45FJFPAC6XI3SVGIJM.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/2XXTNU5LWRBRLACWMMRJ5KTHCY.JPG)