Women’s rights organization Terre des Femmes estimates that 65,000 women affected by female genital mutilation (FGM) are living in Germany. DW’s Kate Brady met one Somali woman who is calling for an end to the practice.

“I was about 11 or 12 years old. Several people held me down. Then they cut me. They laid me on the table. I can still see the image. I had such horrific pain. Then they sewed me together. They tied my legs together for a month so that the wound would heal.”

Following an increase of arrivals from countries where female genital mutilation is most prevalent (FGM), the women’s rights organization Terre des Femmes estimates that 65,000 affected women are now living in Germany — an increase of 12 percent on last year.

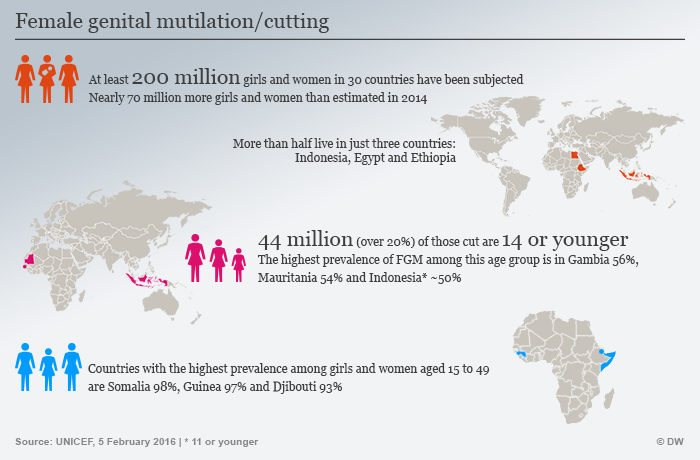

Thirty-six-year-old Ifrah* is one of them. According to the UN’s children’s agency, UNICEF, her homeland, Somalia, has the highest prevalence of FGM of any predominantly Arab country, with an estimated 98 percent of females between 15 and 49 years having undergone the practice.

The brutal practice is seen as a prerequisite for marriage in some countries

‘A knife and a razor’

“The procedure is done by a so-called ‘cutter’,” Ifrah recalls. “They have no idea what they’re doing. They just have a knife and a razor and they cut.”

Procedures for “female circumcision” vary. They range from damaging the clitoris to sewing up the vaginal opening. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 200 million women worldwide are living with the consequences of FGM. Chronic menstrual pain, recurring infection, difficulties in childbirth, loss of sexuality — the effects, both physical and mental, are lifelong. Some can prove to be fatal: Ifrah’s sister died at the age of nine from blood loss during the procedure.

In some communities, the brutal practice is considered a rite of passage and a prerequisite for marriage.

“In my community, the belief is that if a woman isn’t sewn up, any man could have been there,” Ifrah says, her eyes glancing towards her lap.

Limited medical expertise

After two and a half years in Germany, Ifrah is seeking advice at Berlin’s Desert Flower Center. The clinic, funded by donations, offers reconstructive surgery, consultation and holistic treatment for women affected by FGM.

Since it opened in 2013, Dr. Cornelia Strunz has advised some 300 women. But the clinic in southwest Berlin is an exception. Faced with a growing number of women suffering the effects of FGM, Germany’s services and expertise in FGM are still limited.

“When I studied medicine, FGM wasn’t covered in the subjects,” says Dr. Strunz. “But I know this is changing, and I hope that trend continues. However, I still meet colleagues who either know very little or absolutely nothing about female genital mutilation.”

In a statement to Deutsche Welle, the German ministry for women’s affairs said it planned to work more closely with youth welfare offices over the current legislative period. Whether there will be financial aid to help support groups for affected women wasn’t clear. The Justice Ministry was unavailable to comment.

‘Vacation circumcision’

But even if the government steps up its action to support women affected by the practice, there’s little it or authorities can do about cases where young girls are taken back to their parents’ home country for a “vacation circumcision.” Terre des Femmes estimates that some 15,500 girls living in Germany are in danger of being forced to undergo FGM under such circumstances.

That’s where society has a role to play, says Terre des Femmes’ Charlotte Weil.

“The only way to really gauge what’s going on is to have a vigilant society. That particularly means people who work in close contact with families — volunteers, teachers having to do with parents who might potentially subject their daughter to FGM. These people should be particularly attentive,” Weil says.

She says the government also needs to provide financial aid to volunteer support networks.

“It’s important, however, to not tar every family with the same brush,” she adds.

For Ifrah, however, the fear of her daughters suffering the same fate as her 11-year-old self has already become a reality.

“My three eldest daughters who still live in Somalia — they weren’t so lucky,” Ifrah says. “They were ‘circumcised.’ But my 3-year-old hasn’t been.”

From a nearby bench where she’s waiting with a friend, Ifrah’s 3-year-old calls over to her mother: “Look!” she giggles, tapping her tiny heeled shoes on the cobbles.

‘That was our fate’

“If we’re ever sent back to Somalia, I’m 100 percent sure that her grandparents will make her undergo the procedure,” Ifrah says.

For her eldest three daughters, it’s already too late.

“That was our fate,” Ifrah says. “Those of us who had to experience that. But I’m a fighter. I hope that these women [that have undergone FMG] are healthy. And I hope that at some point this ritual will be stopped.”

* The name of the young woman was changed to Ifrah In the interests of privacy.

DW