The Court of Appeal has upheld the deportation of a refugee known only as AM who entered the UK in 1987 aged 11. Having grown up and been educated in the UK, AM held several jobs at different times, had been married and had three estranged British children. He also had 27 criminal convictions to his name, the most recent of which was a robbery leading to a two-year prison sentence. The case is AM (Somalia) v The Secretary of State for the Home Department [2019] EWCA Civ 774.

The UK Borders Act 2007 obliges the Home Office to deport any foreign national who receives a sentence of 12 months or more. There are some limited exceptions to this requirement, including where deportation would breach EU law (while that still applies), the UN Refugee Convention, or human rights law.

AM attempted to rely on the Refugee Convention and human rights law but ultimately failed and now faces deportation.

Refugee Convention and deportation

Although AM had been recognised as a refugee in 1989 and still held refugee status all these years later (unlike refugees who later naturalise as British, for example), there were two reasons this did not help him.

Firstly, the Refugee Convention does not provide permanent protection. In international law it is a temporary form of status. If conditions in a refugee’s country of origin improve so that it is safe to return, refugee status can be withdrawn. This is called “cessation” and is governed by Article 1C of the Refugee Convention. It is not based on the personal conduct of the refugee but rather on conditions in the country of origin.

Most host countries do not in fact force refugees to return once they have settled down because it would be inhumane. The UK currently grants quasi-permanent settlement to refugees after five years of residence. However, this status is revocable.

Thus it was with AM. The Home Office decided that Somalia is now safe for AM to return to.

It would seem to follow as a matter of logic and consistency that all other Somali refugees in a similar situation (AM seems to have been born in Somaliland) should also be returned to Somalia. This point was made forcefully by immigration inspector David Bolt in a report in 2018, where he found that personal conduct was in fact being used as an excuse by the Home Office to cease refugee status supposedly on the grounds it was safe to return. Mr Bolt described the Home Office’s approach as “egregiously” inconsistent. The practice has nonetheless continued, and as we shall see in a moment it is simply unnecessary as well as offending against the structure of the Refugee Convention.

The second reason the Refugee Convention did not protect AM from deportation is that the Convention does not protect very serious criminals. Article 1F of the Convention excludes certain individuals from refugee status in the first place and Article 33(2) of the Convention allows for termination of refugee status on the basis of the personal conduct of the refugee in the host country. The Article 33(2) test is whether the refugee “having been convicted by a final judgment of a particularly serious crime, constitutes a danger to the community of that country.” The Home Office concluded that AM met this test.

Human rights and deportation

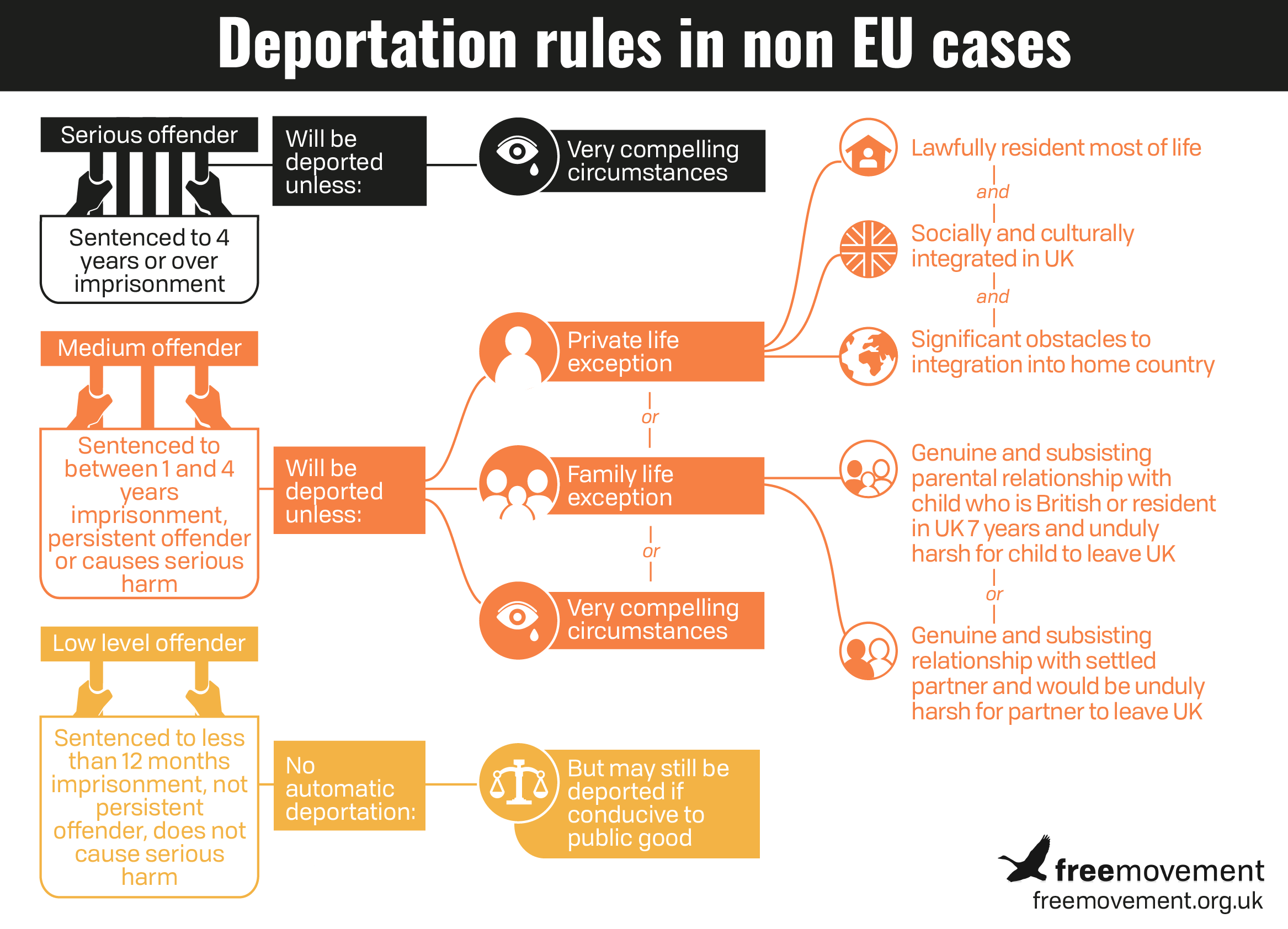

Human rights law provides very limited protection against deportation where a prison sentence in excess of 12 months has been imposed. As our infographic from our course on deportation shows, the conditions to meet are tightly drawn:

In this case, AM relied argued that after 30 years of residence, several jobs, a marriage and three children, he was “socially and culturally integrated in the United Kingdom” and that there would be “very significant obstacles” to his integration in Somaliland, which he could barely remember and where he had no real or meaningful links. Mr Gill QC on AM’s behalf argued that “[g]ood or bad, whatever he is, is the product of this society“.

This was quite a good argument, you might have thought.

However, the Home Office and judges concluded that he had been integrated but was no longer so. The Court of Appeal endorsed the immigration tribunal’s controversial decision in Bossade [2015] UKUT 415 (IAC).

The effect of this approach is to render the exception to deportation a Catch-22 style mirage; just when a person might need it because of criminal offending, that very criminal offending means that the exception is no longer available. To be fair, though, Lady Justice Gloster does say that time spent in prison will not necessarily result in a break in an offender’s social and cultural integration.

Some readers may be left suspecting that the colour of AM’s skin was all too relevant. Had AM been white and British, no-one would even think of suggesting that he was not “integrated”. The question would be considered nonsensical. As we have seen in the Shamima Begum case, integration and belonging are conditional even for those who are British when their skin is insufficiently white.

While the law applied here is an Act of Parliament, the judges in Bossadeand AM had choices to make about how to interpret and apply this provision. They chose to find that the “integration” of a migrant resident for 30 years is conditional on good behaviour.

Refusal of adjournment and procedural fairness

Prior to the full hearing of his appeal in the First-tier Tribunal, AM had secured a direction from the tribunal that the Home Office disclose his OASys report. An OASys report is essentially a detailed probation service report on the risk of reoffending. AM argued that risk of reoffending was highly relevant to the issue of whether AM was integrated or not. It was also potentially relevant to whether AM was a “danger to the community” and therefore excluded from the protection of the Refugee Convention.

The Home Office failed to comply with the direction. AM applied for an adjournment of his appeal to give the Home Office time to comply, but this adjournment request was refused.

Let us just pause here for a moment to reflect. The tribunal gave a direction. The Home Office ignored it. The tribunal then decided to proceed with the appeal anyway even though its own direction had been ignored, thus depriving itself of evidence that might have assisted the appellant. While the tribunal’s lack of self-respect and apparent indifference to procedural fairness may seem surprising to those not accustomed to immigration litigation, I can assure readers that it is in fact standard practice.

On appeal to the Upper Tribunal, the judge expressed “concern” that the direction had been ignored and suggested that the reasons for non compliance should be investigated. But she held that there was no procedural unfairness.

At this point, the Home Office had still failed to disclose the OASys report, despite there being a protocol in place between the Home Office and National Offender Management Service since at least 2014 enabling such disclosure. The report was finally disclosed before the Court of Appeal.

Giving the leading judgment, Gloster LJ held that the OASys report could not have been relevant to the decision to revoke refugee status on the basis of personal behaviour because it was not that decision that was under appeal. Nor would it have helped with AM’s human rights case, apparently, although the reasons for this seem rather unclear.

Gloster LJ also found that AM had left it too late to complain of procedural unfairness by leaving it late to to request the OASys report. Males LJ disagreed on this point, and Hamblen LJ gave it a limited endorsement.

The case is a troubling one, both on the issue of conditional integration and on the issue of procedural fairness.

Free Movement