There’s no doubt that Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s first five months in office have brought enormous change to the country. He’s also been hailed for shepherding Ethiopia to a historic peace agreement with neighbour Eritrea.

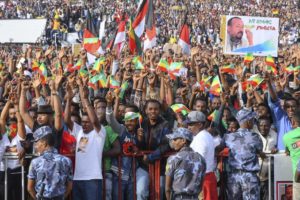

Thanks to Abiy’s astounding short-term gains, Ethiopians both at home and abroad are feeling hopeful.

But all is not well in Ethiopia. Ethnic tensions and violence are on the rise. Ethnic conflicts are not new, but the levels of violence being witnessed today are very disturbing.

Ethiopia has more than 80 ethnic groups. Despite recent improvements, it also has a weak economy and an overwhelmingly poor citizenry. If Abiy wants to make a genuine attempt at real democracy he must do away with tribal politics and make stronger strides towards national unity.

Ethnic tension

The renewed ethnic tension is unfolding on several fronts.

Ethnic Amharas who were evicted and displaced from the Benshangul-Gumuz and Oromia regions are yet to receive government assistance. Most of the ethnic Oromos who were evicted in their hundreds of thousands from Ethiopia’s Somali region in 2017 remain displaced.

The ethnic Somalis who were evicted from Oromia in retaliation are also still displaced. Ethnic Gedeos who were evicted from Oromia’s Guji areas are now living in appalling conditions in schools, closed factories and temporary camps.

Hundreds of innocent Ethiopians have died in the southern cities of Awassa and Sodo because of ethic violence.

And in the past two weeks alone, dozens of Ethiopians from the Gamo, Ghuraghe, and Dorze groups around the capital city, Addis Ababa, were targeted and killed by unidentified assailants.

A rally that was organised in Addis Ababa to protest the killings was violently dispersed by police. The media reported that some residents were killed by government security forces.

To understand the latest events, it’s necessary to look to Ethiopia’s history. Ethnic tensions have simmered – and often boiled over – for decades. Some of the earliest signs can be traced back to 1991, when former president Colonel Mengistu Hailemariam’s regime was removed from power.

Causes of the violence

When his military regime was overthrown in 1991, a hastily organised coalition seized power in the capital.

The coalition, known as the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, was made up of four ethnic parties: the Oromo Peoples’ Democratic Organisation, Amhara National Democratic Movement, Southern Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement, and the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front.

Soon after the coalition came together, it introduced an ethnic federal system of governance to try and address historic ethnic grievances by giving Ethiopia’s different regions the chance to administer themselves. This federal system allowed regions to organise along tribal lines. It also led to the rise of ethno-nationalist movements, which eventually weakened Ethiopia’s national unity.

Ethnic intolerance grew and gained momentum, and ethnic violence became a permanent fixture of Ethiopian politics.

Ethnic groups have, over the past few decades of coalition rule, staked claims to territories administered by other tribes. Ethnic Amharas, for instance, have claimed ownership of the Wolqait and Raya territories in northwestern Ethiopia, leading to tensions with the Tigray region, which currently administers these areas. Violence has often erupted over the claim.

Ethiopia’s Somali and Oromo communities have also seen their fair share of violence over ownership of ancestral and pastoral land.

So, the issues of federal governance, negative ethnicity, and debates over land ownership have been a longstanding thorn in the Ethiopian leadership’s flesh. What remains to be seen is how Abiy’s administration will deal with it. Can the new premier resolve these issues and keep his reforms agenda on course?

Ahmed’s options

Despite Ethiopians’ optimism, the simple answer is no. And the reason is this: the ruling coalition is still a conglomeration of four ethno-nationalist parties. Despite Ahmed’s newly adopted reforms, which lean towards the rights of the individual and citizenship politics, the ruling coalition remains fixated on the group-rights agenda. This agenda has always privileged division over unity.

The Oromo Democratic Party, for instance, still advocates a controversial idea known as Oromia’s Special Interest in Addis Ababa.

The organisation is the most powerful party in the ruling coalition today. Its members have made a political and constitutional claim to Addis Ababa because it is an enclave located in the State of Oromia. The city now doubles as the capital of Oromia despite the fact that less than 20% of its residents are ethnic Oromos.

This has led to tensions between ethnic Oromos, who are the minority in Addis, and other ethnic groups like the Amhara, who are the overwhelming majority in the city.

Such ethnic rivalries and conflicts are common in Africa. However, Ethiopia can be singled out for the manner in which these rivalries have played out. The ethnic federal arrangement has given ethnic parties and their politics the legal foundation to flourish.

Unfortunately, when ethnic interests and ethnic politics become the modus operandi of the ruling coalition and opposition elites, the challenges to a country can quickly become insurmountable.

Prime Minister Abiy must now take measures to reduce such conflicts and address ethnic tensions. Creating a framework whereby cultural, religious, and social organisations could utilise the rich social capital at their disposal would be crucial. Moreover, Abiy should not shy away from the possibility of constitutional change. This would allow for the articles that have entrenched ethnic divisions to be amended. Finally, Abiy’s administration’s should focus on building much-needed democratic institutions because a functioning democracy will solve most of Ethiopia’s problems.

The Conversation