By Eleanor Beevor

It’s been a breathless few weeks for the Horn of Africa in general, and for Somalia in particular. A historic agreement was signed between Somalia, Eritrea and Ethiopia to end all hostilities between them. Straight afterwards, Eritrea reconciled with Djibouti.

For the first time in decades, it seems that the regional capitals are sincerely ready to make peace, and to build on it. But though this is no doubt good news, it will not solve Somalia’s internal strife. This week, Somalia’s future is looking extremely uncertain. And that is – at least partly – because it has become embroiled in the Gulf crisis that has pitted Qatar against its neighbours.

Somalia is meant to be getting ready to take charge of its own security. The African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) was coined as a “peace support” mission in 2007, to help Somali forces oust the Al-Qaeda linked Al Shabaab insurgent group from the capital Mogadishu. But its six-month mandate kept being expanded, and a decade later it is still there. It is now comprised of over 21,000 troops from six contributing African nations.

Whilst it has been indispensable in pushing back Al Shabaab and in providing some fragile security, it can’t by any standards be thought of as a “support” mission anymore. AMISOM effectively replaced the Somali National Army (SNA) in combatting Al Shabaab. But now, it is talking about winding back its presence in the country.

AMISOM wants to withdraw a thousand troops by February 2019, and aims to be handing back all security responsibilities to the SNA and leaving Somalia by 2020 to 2021.

There are no guarantees that this will go ahead as planned. Abdullahi Boru, a Somalia analyst, told Al Bawaba:

“While Amisom has indicated its withdrawal, the situation in the Horn of Africa has seen sea change over the last few months, that, that decision could be reversed. I am not suggesting anything has been agreed as of yet, but having Ethiopia, Somalia and Eritrea (which has been accused of supporting Al Shabaab) on side will have a significant impact on the security situation on the ground. At the practical level, withdrawal of troops when the security situation on the ground has not changed will increase the number of attacks by Al Shabaab, and other opportunistic criminal outfits.”

But however AMISOM’s departure eventually pans out, the SNA is still a very long way from ready to assume its duties. The army has been provided with training by a number of countries – including the US, the UK, Turkey, Sudan and Egypt. But each of these militaries has differences, from how to salute to different chains of command. Reassembling the SNA into a coherent unit after it has been trained in myriad different ways will be an uphill struggle.

Add to that the fact that the SNA is chronically low on resources. Somali security forces are short of everything from radios to paper and pencils. Their access to weapons is ad hoc, and corruption is rife. How things will look when the SNA assumes control from AMISOM is anybody’s guess, but it’s safe to say that it won’t be easy for them to hold the existing gains made against Al Shabaab.

But a bigger security problem could be on the horizon, and it ironically comes from within Somalia’s own government system. In the past few days, five of the country’s federal states, including the semi-autonomous region of Puntland, have severed ties with the Federal Government of President Mohammed Abdullahi Farmaajo. The leaders of the states in question say that the move is to put pressure on the government, and push it to meet its goals.

Farmaajo’s government is aiming for the country to have its first election with universal suffrage – “One Person, One Vote” – since the decades-long Siad Barre dictatorship. So far, the security situation has rendered this impossible. Farmaajo’s government was elected by a complex system of selection by clan leaders, as a preliminary move towards universal elections. There are a lot of doubts about whether this will be possible within the next two years. But if the government fails, it will be a major blow to its credibility.

The problem is that the Somali federal system, and the country’s complex colonial history, means that there is only so much will for unity anyway. States regularly pursue their own agendas, and greater autonomy. And while there are plenty of legitimate grievances to be had with Mogadishu, it’s the country’s inconsistent relationships with the Gulf states that is cleaving the deepest divisions in Somalia right now.

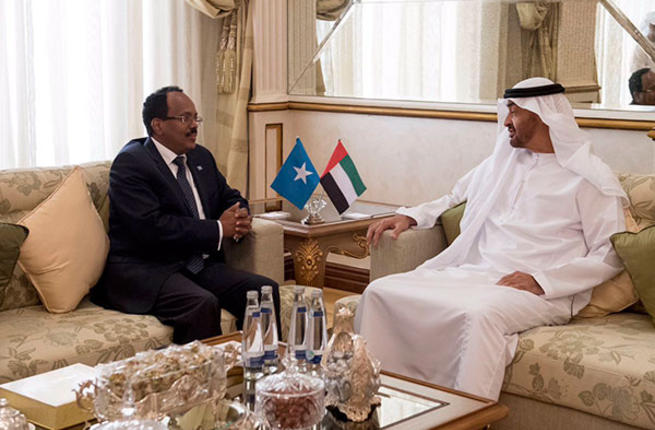

Up until last April, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates were some of the Farmaajo government’s closest international partners. The UAE was Somalia’s largest trading partner, and Saudi Arabia bought the majority of the livestock that Somalia exports.

However, when these two countries led the blockade of Qatar in 2017, they pushed for all countries in the region to sever ties with Doha. But unlike many countries which kept quiet and maintained their links to Doha anyway, Farmaajo seemed to feel the need to openly declare Somalia’s neutrality in the Gulf crisis. (That may have been a gesture of quasi-solidarity with Turkey, which is Somalia’s largest foreign investor).

The scene of the horrific October 2017 bombing by Al Shabaab in Mogadishu (AFP)

This wasn’t good enough for the blockading states, and relations began to sour. Tensions between Farmaajo’s government and the UAE were already rising due to the latter’s relentless, and divisive port building campaign around the Horn of Africa. The UAE is upsetting Mogadishu by developing its own ports in Somali regions that are striving for autonomy from Somalia. One in Berbera, Somaliland, a self-declared independent state, and the other at Bosaso, in the semi-autonomous region of Puntland.

The Federal Government sees this as undermining its authority vis-a-vis the state authorities. And they wouldn’t be wrong to do so – the UAE unsurprisingly likes to deal with state rather than central authorities, which give it a freer hand to pursue its interests.

But things came to a head in April this year when an Emirati plane stuffed with $10 million in cash was found on a Mogadishu runway. Whilst the UAE insisted this was for the salaries of the soldiers it was training, the Federal Government didn’t buy it, and assumed the money was for influencing state politicians. The UAE pulled out its training support for the SNA in response, and its relations with Mogadishu are on ice. But Qatar has seemingly rushed in to fill the vacuum the UAE left.

Farmaajo was courted with a state visit to Doha a month later, on which Qatar pledged hundreds of millions of dollars worth of aid to Somalia. And there is reason to believe Qatar’s influence is even further reaching. In recent weeks, the Somali intelligence agency NISA sacked a former deputy director for revealing that Al Shabaab had infiltrated the agency. His replacement is the former Al Jazeera bureau chief for Somalia, who is widely suspected to be pushing Qatari interests in his new position.

To whatever extent this is true, the suspicion alone is a troubling development for Somali security. One of the key drivers of the current fallout between the striking states and Farmaajo’s Federal Government is disagreement over UAE relations, since federal states have a lot to gain or lose depending on their relationship with it. This is particularly true for the semi-autonomous regions, who are looking to leverage the Gulf conflict for their own interests. Abdullahi Boru added:

“Somaliland and Puntland have been vying for control of the Sool and Sanaag regions because of their strategic link to the Gulf of Aden to the Ethiopian border. The increase of interest from the Gulf Countries post their fall out, has embolden the devolved authorities.”

Equally, the UAE is proving itself adept at circumventing Mogadishu’s rule by dealing directly with state authorities. If Qatar is suspected of having too much influence in the Federal Government, the UAE will play states off against it, and vice versa. But this could come at a very significant security cost as AMISOM works to extract itself from Somalia.

The SNA is already fractured. But the army cannot operate effectively across a nation if individual states will not cooperate with the central government. And this is a weakness that Al Shabaab, an insurgency with deep roots in the Somali population, and with a history of innovatively undermining the government, will be sure to exploit.

Al Bawaba