Girls with disabilities in Ethiopia have been sexually assaulted and are feared for being under the spell of witchcraft.

Amhara, Ethiopia – Newly elected Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has been praised for his recent negotiations culminating in peace with Eritrea, but still has to solve harsh realities at home.

Thousands of boys and girls with disabilities in Ethiopia are invisible in government statistics, unable to access health services, discriminated against by society and trapped in a cycle of poverty and violence.

A report from UNFPA and the Population Council highlights that one in every three girls living with disabilities has been sexually assaulted. They also face systematic and violent abuse at home and in their communities; they’re blamed for being different and feared because they’re seen to be under the spell of witchcraft.

Eniyat Belete, 17, has been blind since birth. In her village, as in many other towns all over Ethiopia, disability comes with a heavy stigma.

“They believe I was cursed with blindness because God was angry,” explains the teenager.

Fisseha Arage Haile, himself blind, works as a special needs and inclusive education expert for the South Gondar Zone Education Office.

He confirms that teenagers with disabilities are largely excluded from education, health and social welfare services. The Charities and Societies Proclamation (CSP) law makes it impossible for NGOs and other civil societies to operate in the country, which compounds the severe gap in service provision.

Specialised health and rehabilitation services are not accessible to the majority of the population and medical aids are expensive: crutches cost $8 on average and a wheelchair costs $224, unaffordable for most Ethiopians.

Only a fraction of children with disabilities are enrolled in formal education. Ethiopia, with a population over 100 million, only has 164 schools that serve students with hearing, visual and intellectual impairments. There are only two schools for students with autism, both of which are in Addis Ababa.

“There is still much work to be done until we can truly speak of an inclusive society,” Haile, an avid advocate of disability rights and changing the system from within, sighs: “As it is now, it is only inclusive by name.”

![Eniyat Belete (right) is 17. She has been blind since birth. In her village, as in many other towns all over Ethiopia, disability comes with a heavy stigma. "They believe I was cursed with blindness because God was angry," explains the teenager. Despite the neighbours' prejudice against her daughter's impairment, her mother says: "I will support her education, whatever financial sacrifice it may take. God gave her to us this way, and we love her [the way she is]." [Nathalie Bertrams/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2018/9/18/8adc64db42114ddbb616826546752eb6_8.jpg)

![Eniyat leans on her sister’s shoulder as they walk to their home in the hills of Selamaya, a village in the highlands of North Gondar. Eniyat needs her sister's help with the daily 30-minute hike from school. Girls with impairments are vulnerable to abuse, as Eniyat puts it: "It is not like we can see our attacker." [Nathalie Bertrams/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2018/9/18/2012a60cbedf4c07b0832022084013c4_8.jpg)

![The special needs educator visualises how to spell the alphabet in sign language, letter by letter. There is a lack of teachers, classrooms and funding for special needs education, so space and resources often have to be shared. In the future, Eniyat hopes to move to Ebenat, a nearby town, to complete 10th grade and pursue her dream of becoming a special needs teacher herself. [Nathalie Bertrams/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2018/9/18/fd17d960f9974cfc9d0d2b63ba5eccb3_8.jpg)

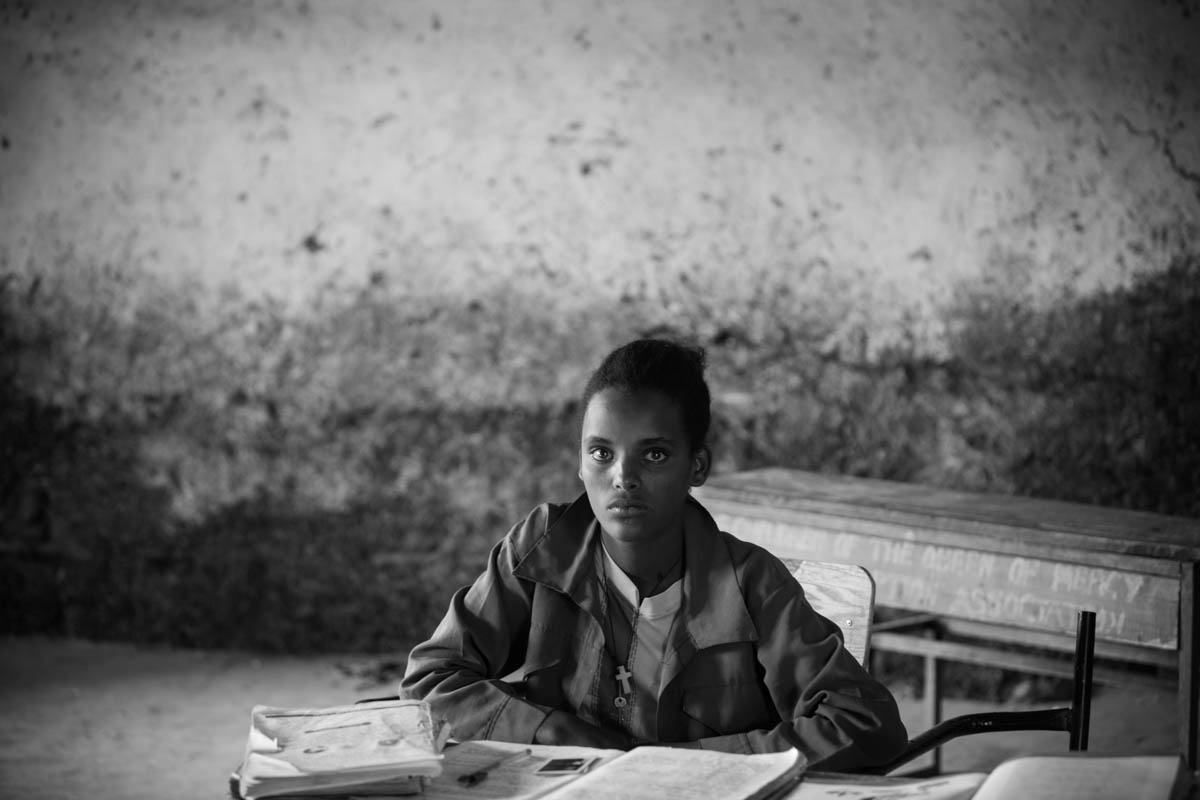

![Tapping on her friend's shoulder to ask how she did on her test, Meseret says: "It is just too difficult. I can't hear what the teachers say, so I just copy from the blackboard. And they don’t help me at all, they even get angry when I don't understand. How am I supposed to do well on this stupid test?" After grade 4, only 6,000 students with disabilities attend high school countrywide. [Nathalie Bertrams/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2018/9/18/993a2ebd20bd49ab9a26feaf45f708df_8.jpg)

![Misaye Niguse, a 19-year-old with carefully plaited cornrows, has left home. Her father, a subsistence farmer, found her shelter in a church-supported charity for the poor, which houses people living with disabilities, as well as orphans and widows. As she is going to primary school, the government provides her with a special needs student’s stipend of $7 a month. "It is barely enough for injera," says the young woman, adding that she often can't even afford three daily rations of the staple sourdough flatbread. [Nathalie Bertrams/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2018/9/18/35a2e79574604f43b8e82c96279477bc_8.jpg)

!["Debre Tabor is dangerous," Misaye explains. When she heads to school, she crosses a busy road packed with honking, blue taxis and flashy tuk-tuks. She is terrified of being hit by a passing car or truck. "Drivers don’t ever slow down," Misaye says. "They don’t even see me." To navigate the road, she clutches the arm of her best friend and guide, who is also visually challenged but, unlike Misaye, is not completely blind. [Nathalie Bertrams/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2018/9/18/0174797cae2348b999990b272debfc15_8.jpg)

![Yirdaw Nehmet, a farmer living in the hills of Ebenat, sits on a bench next to his daughter Yetreunesh. The two share an intimate language that no one else can understand; the shy 10-year-old is nearly deaf and has never learned sign language. Her father is the only one who can communicate with her. [Nathalie Bertrams/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2018/9/18/5ec7770256024bb58f7a99277f720527_8.jpg)

!["When Yetreunesh was a baby, she travelled on her mother's back, exposed to the wind and the sun," Yirdaw says explaining his daughter's condition. Yirdaw never consulted a doctor; it would have been too expensive for the farmer, whose harvest has been meagre due to recurrent drought. Research shows that almost two in three children with visual impairments in Ethiopia acquired them from preventable diseases. [Nathalie Bertrams/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2018/9/18/ba8d52aaa0314f729c8f8279c05e5ed2_8.jpg)

![Without adaptations for their disabilities, 'living alone is dangerous,' says Addisie (middle), the younger of two girls, emphasising their constant worries. "There could be a fire, an electrical explosion, we wouldn’t be able to hear it." Like their little brother, both sisters rather stay at home after school for fear of something happening to them. [Nathalie Bertrams/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2018/9/18/04d72bcf1db54369995f5b2c6f5cba5f_8.jpg)

![Some men, Addisie says, believe that "girls like us" are free from HIV and other diseases, making them a preferred target of sexual abuse. Reinforcing the men's motives is that "they think we are cursed by the ancestors anyway." That means the men think girls with a disability have no right to resist. [Nathalie Bertrams/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2018/9/18/a6a844f9f2d74cf38c59fb68716fbf4b_8.jpg)

![Fisseha Arage Haile works for the Ministry of Education. When he was a student, he taped his teacher speaking on a portable recorder so he could replay the lesson at home. Some of his teachers would hit him as they did not like to be recorded when "they were speaking politically". [Nathalie Bertrams/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2018/9/18/c3bed58643a247d09e9a8b3527b33bcc_8.jpg)

AL Jazeera

![At home, her family adapts life to fit Eniyat's needs. While traditionally all girls help their mothers fetch water, clean and cook, her role in the household is limited: she takes care of her sister's baby girl.

[Nathalie Bertrams/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2018/9/18/ee5ab6814dd2463f868c3d4e3fb4c26a_8.jpg)

![Eniyat and the other blind students sit in silence on their pew at the back of the classroom while their teacher works with the deaf children in sign language. Eniyat's school in Selamaya only has one teacher who does not know how to write Braille himself. [Nathalie Bertrams/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2018/9/18/223920ecafe349458156711fcba422e1_8.jpg)

![Misaye is determined to learn Braille. "The government needs to support disabled people more," says the quiet girl with determination. "When I have finished my education, I will become a civil servant and change that." [Nathalie Bertrams/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/Images/2018/9/18/5c1e9d0f26524b93b82dc3df4b95fce9_8.jpg)