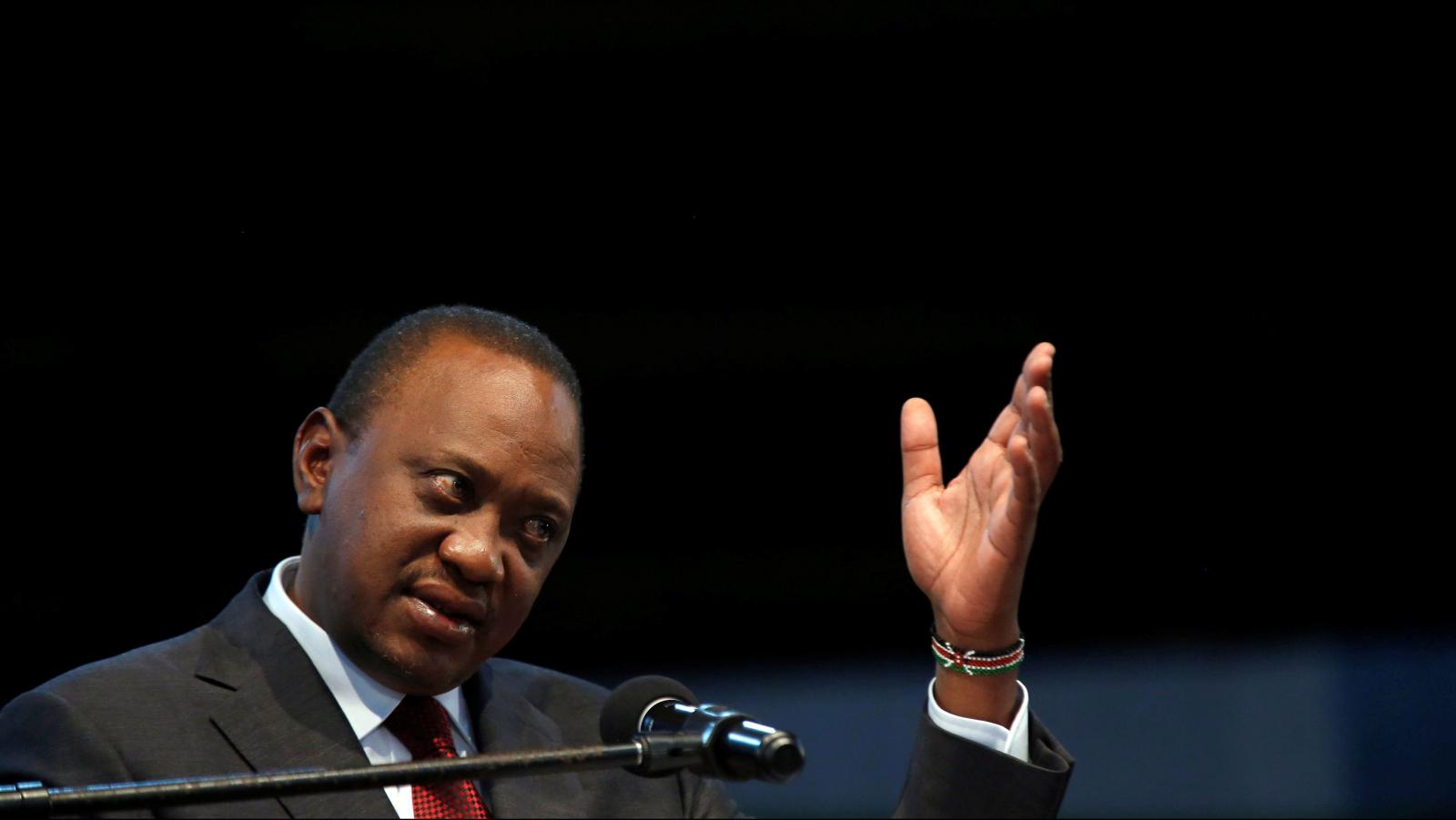

Kenya’s president has lost friends and allies in recent weeks—many, many of them.

Uhuru Kenyatta recently said his administration’s war on corruption cost him supporters but vowed nonetheless to continue efforts to stamp out graft. In the last few weeks, the public prosecutor has ordered the arrest of current and former public officials on charges including abuse of office, conspiracy to steal public funds, and fraudulent compensation claims for land use.

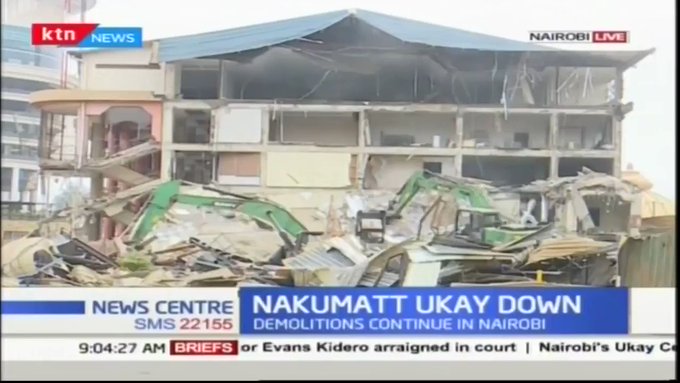

The government also earmarked 4,000 buildings in Nairobi for demolition, claiming they were built illegally on riparian land. And in a bid to stop wastage of resources, Kenyatta issued a directivefreezing the implementation of new projects until all ongoing ones were completed.

Responding to those who called him with complaints, Kenyatta said he told them it was vital to fight impunity to achieve the dream of a better Kenya. “A time has come for us to fight impunity. A time has come for every Kenyan to realize no matter how powerful you think you or how much money you have… That will not save you.”

Kenya is ranked 143 out of 180 on Transparency International’s corruption index, and for years, pervasive graft, cronyism, coupled with ethnic rivalries exploited by political leaders has undermined successive administrations. The lack of public accountability, centralized power, and the absence of strong state agencies have also strengthened officials’ seemingly insatiable appetite for graft. The shift in government sentiment about corruption has led ardent critics to declare that officials were finally outshining themselves.

But it’s unlikely to herald a new dawn for Kenya.

Rooting out corruption and introducing systemic reforms will take more than demolishing a few buildings. This is especially true of Kenyatta’s administration, which former anti-corruption czar John Githongo once called the “most rapacious administration that we have ever had.”

The current fuss over corruption also isn’t new and high profile cases of corruption continue to recur without much action. For instance, the National Youth Service is currently roiled in a $78 million scam involving ghost companies. Yet the state agency was caught in a similar multi-million-dollar scandal in 2014 which involved money laundering and the purchase of sex toys and condom dispensers at inflated prices.

Similar investigations have taken place at the national cereals and produce board both in 2018 and 2010 after brokers took advantage of opaque vetting systems. Allegations of corruption have also defined the country’s power agency for years, with millions of shillings lost over the supply of defective transformers and unaccounted labor and transportation costs.

The entrenched nature of corruption has also reared its ugly head in recent days. On Wednesday (Aug. 15), the Kenya civil aviation authority announced a hotel belonging to deputy president William Ruto was built on a parcel of land it owned. And as Kenyatta ordered a lifestyle audit of all public servants and their families including himself, a preliminary audit showed a third of all workers couldn’t account for how they amassed their wealth.

As both large-scale and petty corruption practice continue, Kenyans remain skeptical about the fight on corruption. A 2015 Afrobarometer survey showed many believed the police, government officials, and lawmakers were the most corrupt. Those assertions were proved real this week when reports surfaced that legislators were paid a mere $100 in the parliament’s toilets to reject a critical probe into corrupt sugar deals.

Quartez