Ethiopia is a rarity in Africa. It has existed in a coherent form for more than 2,000 years and largely escaped European colonization. The country’s lineage — tracing back to the kingdom of Aksum in the first century — makes it stand out among its neighbors, and its advantageous location between the ancient trade routes of Rome and India makes it stand out on a map. The country’s recent push for reform and desire for strategic partnerships in the Horn of Africa provides a timely reason to explore Ethiopia’s geopolitical environment.

The Highland Core and Lowland Periphery

East Africa has three power cores: the Nile River Basin, the Kenyan Highlands and the Ethiopian Highlands. The Ethiopian Highlands — which run roughly from Asmara, the capital of Eritrea, to the center of modern-day Ethiopia in the capital of Addis Ababa, continuing along the Great Rift Valley — have been crucial to Ethiopia’s development. For thousands of years, they protected its peoples from marauding hordes and foreign armies, which would have had to overcome mountains and a harsh desert to invade. The country’s higher elevation also reduced threats from malaria and other diseases, while waterways provided transport arteries. Fertile lowlands made settlements and agriculture viable, supporting a large population base from which governments could draw taxes and labor.

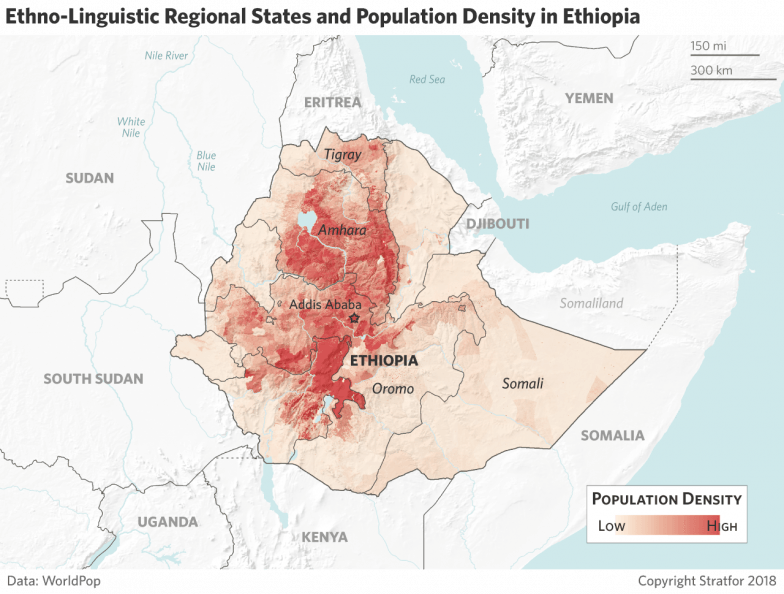

The Tigrinya- and Amharic-speaking peoples who live there have used the highland core’s natural advantages to project power into nearby zones, including the surrounding lowland periphery. The government in Addis Ababa, for example, has long tried to control the ethnic Somali-majority Ogaden region in the east in an effort to weaken a perennial competitor and to buffer its core from potential attacks from the east. As a result, cyclical flare-ups of violence have occurred as Somali nationalist militants strive to reunite the province with Greater Somalia, providing meddling regional powers a conduit to weaken Ethiopia.

Ethiopia and its predecessor states have long grappled with ethnic conflict between different groups vying for control of the country. Given Ethiopia’s large territorial size and geographical barriers, the central government has struggled to exert control over the diverse populations of the hinterlands. Ethnic insurgencies have been a near constant feature of the country’s history, and managing them is a key imperative for its leaders. To that end, they have tried a variety of tactics, from reconciliation to repression. But neighboring states have seized on the issue and supported several of these ethnic insurgencies to keep Ethiopia’s attention on its domestic problems rather than on regional activities. (Ethiopia, likewise, has supported insurgencies against its neighbors).

Ethiopia’s Great Game

Though battles with the peoples of the lowlands have kept it focused inward at times, Ethiopia’s highland core has also managed periodically to project power well beyond its borders. The boom-and-bust cycle of power projection dates back to Aksum’s centurieslong command of trade routes through the Red Sea and the African interior, which enabled the kingdom’s Christian rulers to send delegations to Europe and elephant-mounted troops into southern Arabia in the sixth century. Only with the consolidation of power in northern Arabia around the Islamic caliphate and the redirection of trade routes from the Red Sea toward Damascus, in modern-day Syria, did Aksum begin to lose its hold. Infighting among the Aksumite elite helped create additional problems for the kingdom as Islam spread through the region.

In subsequent periods of history, Addis Ababa has thrown its weight around in the Horn of Africa — for example, by intervening in and occupying war-torn Somalia for more than a decade. But it has not since been able to project power farther afield, onto the Arabian Peninsula, for instance. Instead, Ethiopia (or Abyssinia, as it was known in the Middle Ages) used outside diplomatic and military support — from powers as diverse as Catholic Portugal and Orthodox Russia — to overcome some of its challenges, such as encroaching Italian colonization in the late 19th century, as they arose.

In the modern era, the loss of the coastal province of Eritrea stripped Ethiopia of its access to the sea, increasing the costs of imports and exports and making port access a priority for the country’s leaders. Ethiopia has come to rely on tiny Djibouti, which has harnessed its strategic position on the Bab el-Mandeb strait to great effect, to transport some 95 percent of its imports and exports, an arrangement that exposes its large and growing market to supply chain risk. While Addis Ababa has not had the money in recent decades to finance the multibillion-dollar infrastructure projects it would need to ensure supply chain redundancy, China’s rise as a global economic player has expanded its options. In 2017, for example, a Chinese-funded rail project added another link from the port of Djibouti to Addis Ababa, bypassing a congested and risky road route.

The Abiy Factor

Similarly, the country’s political environment is looking more stable today than it has in recent years, thanks in large part to Abiy Ahmed, who became prime minister in April after months of protests in the country and increased infighting in the ruling coalition. Abiy is a new kind of Ethiopian leader: He is young compared to his predecessors, at 42 years old; he is also a member of the Oromo ethnic group, which has played a prominent role in protests since 2016, and a former military officer. And after the previous administration, backed by ethnic Tigray hard-liners, strove to crack down on dissent, Abiy is reaching out to different ethnic groups, ending draconian security measures, and promising free and fair elections in the years ahead. So far, rebel groups and other dissidents have warmed to his overtures, though Ethiopia’s internal cohesion problems persist.

Abiy’s efforts are notable for their speed, but his strategies for stabilizing his country and the region still follow Ethiopia’s core imperatives. The prime minister, for example, has focused on normalizing relations between Ethiopia and its nemesis, Eritrea, in support of his country’s need for port access. In fact, his government has also increased its stakes in ports in nearby Djibouti, Sudan and Somaliland — a semiautonomous region of Somalia — and promised to forge stronger ties with Somalia itself, all in the name of improved supply chain connectivity.

Ensuring internal ethnic cohesion and port access will remain essential pursuits as Ethiopia embarks on this ambitious journey under Abiy. If it can execute on these imperatives, the country may once again be able to project power beyond the region in the years ahead.

WV