The Kenya government’s recent decision to deny entry visas to Somali officials and impose other restrictions on Somalis risks reopening a long-healed wound of distrust between Nairobi and Mogadishu.

The history of the two neighbouring countries, which are now locked in a maritime dispute, is littered with political and military blunders that seem to inform the mutual suspicion between their peoples.

While Kenya has a legitimate right to adopt any policy it deems necessary for its foreign affairs, its recent actions targeting Somalia, such as the reimposition of the Wajir stopover and denying entry visa to government officials, do demonstrate a short-term, knee-jerk reaction to Somalia’s refusal to withdraw the maritime boundary case from the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Somalia’s decision to sue Kenya was certain to test the relations between Nairobi and Mogadishu, perhaps in a magnitude similar to the 1960s rebellion in the former Northern Frontier District that wanted to join Somalia. Kenya put down that insurgency with brute force, whose effects were still being felt by the inhabitants of that region.

But what worked in the 19th Century is unlikely to work in the 21st Century.

INTEGRITY

Kenya is a nation respected the world over for its relatively vibrant democracy and hospitality. It has hosted Somali refugees, two of who later became prominent in the West — a senator in the US Congress and a minister in Canada.

Kenya has a lot to be proud of today, and it does not have to cede an inch of its territory to another country. Every nation has a duty to defend, with whatever it has, its territorial integrity, including its sea.

So when Kenya accepted to argue its maritime boundary case before ICJ, it was doing its national duty. Like any case in court, however, the verdict could go either way.

Kenyan lawyers did a sterling job, contrary to the claims that they underperformed. The location of the waters in question and the court’s handling of similar cases conspired against Kenya’s defence team.

Kenya, therefore, has to act responsibly should it lose the case. Somalia will always be Kenya’s neighbour.

TRAVEL RESTRICTIONS

It will be irrational for a respected nation, like Kenya, to vent its anger on officials, businesspeople and ordinary Somalis, only because they support the current regime in Mogadishu that refused to open an out-of-court dialogue.

All of Kenya’s actions and statements, even in moments of great anger, should be in line with the virtues of a respected nation. The world is keenly watching.

The travel restrictions should not target Somali officials visiting to attend international meetings in Nairobi.

What Kenya did last month, denying entry visas to Somali officials, was an own goal. Kenya is home to the UN’s only headquarters in Africa. Major international organisations choose Nairobi over other cities in the region, not because they were denied space, but because Kenya is a nation that warmly welcomes foreigners.

Kenya can ill afford to put the hospitality reputation on the line, because of a maritime dispute. The collective punishment to Somalis does not win Kenya more friends, especially when it needs Somalia’s help in rooting out the Al-Shabaab terrorists.

POSSIBILITIES

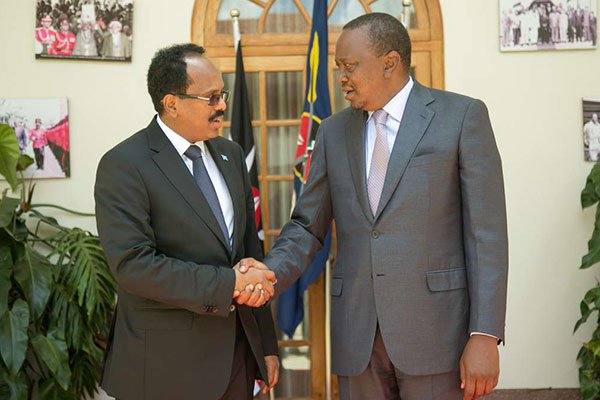

President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed Farmajo, with whom Kenya has disagreed, is not particularly popular at home because of unfulfilled promises. Kenya’s actions could easily turn him into a national hero.

If Somalia wins the ICJ case and President Farmajo gets re-elected in 2021, he will — if the current antagonism continues — likely try to turn the tables on Kenya for its past actions against its citizens.

Kenya’s foreign policy toward Somalia should look beyond the ICJ verdict and think of how to coexist peacefully.

Other countries with similar maritime disputes, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Cote d’Ivoire and Nigeria and Cameroon, were able to move on after the bitter disagreements.

Any other policy that sanctions the scorched earth tactics of the 19th Century is bound to fail. Losing about 100 square kilometres may be painful, but Kenya cannot afford to be like a bull in a China shop, violate human rights and disregard good neighbourliness, to express anger.

(Mr Abdisamad is an analyst with the Nairobi-based Southlink Consultants: abdiwahababdisamad@gmail.com)