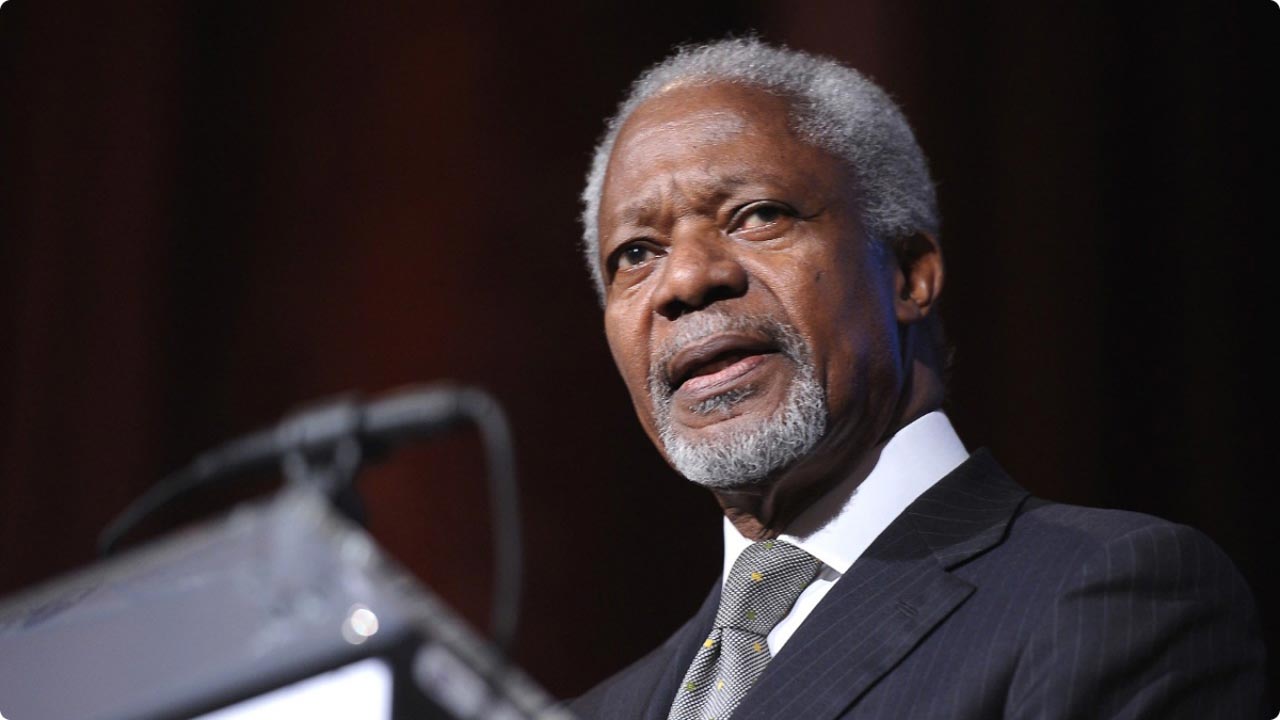

Ghana’s Kofi Annan, whose death at the age of 80 was announced on Saturday, was the first black African to serve as Secretary-General of the United Nations (UN), between 1997 and 2006. He shared the Nobel Peace Prize with the UN in 2001, though his most noteworthy mediation was in brokering a settlement in violence-stricken Kenya in 2008, failing in Syria four years later. During his ten-year tenure as Secretary-General, the Ghanaian diplomat courageously, but perhaps naïvely, championed the cause of “humanitarian intervention.” After a steep decline in the mid-1990s, peacekeeping increased again by 2005 to around 80,000 troops. African countries like Sudan, the Congo, Liberia, Ethiopia/Eritrea, and Côte d’Ivoire were the main beneficiaries.

Annan also moved the UN bureaucracy from its creative inertia to embrace views and actors from outside the system: mainly civil society and the private sector. At the time of his appointment, Annan was widely regarded as a competent administrator who had climbed up the UN system after a 30-year career spanning the fields of finance, personnel, health, refugees, and peacekeeping. He was soft-spoken, and, like the Burmese Secretary-General between 1961 and 1971, U Thant, unflappably calm. He seemed, at first, to be – like martyred Swedish Secretary-General between 1953 and 1961, Dag Hammarskjöld – painfully shy and somewhat uncomfortable in the glare of the media cameras. The Ghanaian appeared to be better suited to the discreet role of a faceless bureaucrat than the high-profile role of a prophetic statesman. But Annan’s mild-mannered side masked a tough interior and a quiet determination to achieve his goals.

In the Byzantine world of UN politics, various informal interest groups battle each other for plum posts. Annan appeared to have little patience for this kind of intrigue, believing instead in a charmingly antiquated version of meritocracy in this world of egocentric godfathers. He also seemed to have made few political enemies during his ascent to the top: a truly impressive feat in the often ruthless political environment of jostling Lords of the Manor who jealously guard their bureaucratic fiefdoms.

Annan’s predecessor as UN Secretary-General was Egyptian scholar-diplomat, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, who held the post between 1992 and 1996, and died in 2016. While Annan was naturally calm and conciliatory, Boutros-Ghali was stubborn and studious; where Annan was a bureaucratic creature of the UN system, and lived mostly in Western capitals, Boutros-Ghali – a former professor – was the most intellectually accomplished Secretary-General in the history of the office and deeply steeped in African politics, having served as Egypt’s deputy foreign minister. Where Boutros-Ghali was arrogant and cerebral, Annan was affable and charming. Where Boutros-Ghali was seen by his staff as an aloof, pompous Pharaoh, Annan was regarded as an accessible, personable Prophet. He and his Swedish wife, Nane (he married her in 1984 after divorcing his first wife, Titi Alakija with whom he had a son, Kojo, and daughter, Ama), soon became regular New York socialites in contrast to the reclusive Boutros-Ghali.

Annan had studied at American institutions – Macalaster College and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology – and was effectively propelled into the top UN job by Washington. Astonishingly, he worked with the Americans as they plotted the removal of the first African Secretary-General, Boutros-Ghali. The Ghanaian thus never shook off the image among many Southern diplomats of being an American poodle. Before becoming Secretary-General, Annan had served as UN Undersecretary-General for Peacekeeping under Boutros-Ghali in a period that saw monumental blunders in Bosnia and Rwanda which did great damage to the UN’s and his own personal reputation. Independent reports in 1999 criticised Annan and his officials for a lack of courage in both failures.

The genocide in Rwanda in which 800,000 people perished, in particular, appeared to have personally scarred Annan, and dogged his historical legacy. Perhaps as a result of a sense of guilt from both debacles; as UN Secretary-General, he consistently championed “humanitarian intervention.” Many leaders in the global South, however, criticised Annan’s promotion of an idea that they saw as potentially allowing powerful states to launch self-interested interventions. These concerns appeared to have been confirmed by the widely condemned American-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, launched without UN Security Council approval.

Annan’s 2005 reform efforts established an ineffectual Peace-building Commission, a still contentious Human Rights Council, and the concept of the “responsibility to protect” which was widely seen to have been manipulated by Paris, London, and Washington to launch a “regime change” intervention in Libya in 2011. Annan’s reforms of the UN bureaucracy were methodical rather than revolutionary, continuing the reduction of staff began under his predecessor and initiating efforts at better coordination among UN departments. The Ghanaian was, however, accused of serious management failures in the “Oil-for Food” programme in Iraq. Annan’s troubled final years in office saw him rendered a lame duck by the U.S., the country that had done the most to anoint him Secretary-General. He finally and painfully discovered the ancient wisdom: that one needs a long spoon to sup with the devil.

Prof. Adebajo is director, Institute for Pan-African Thought and Conversation, University of Johannesburg, South Africa.

By Adekeye Adebajo