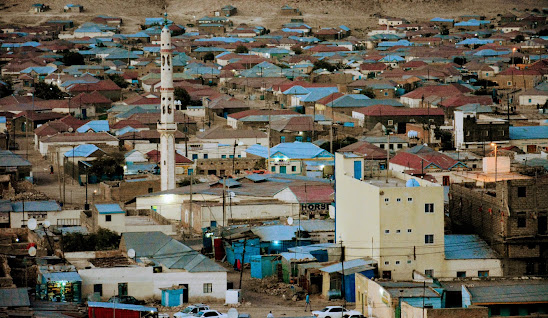

In the often turbulent Horn of Africa, Somaliland has established a reputation as an island of peace, democracy, and stability. Recent conflict in Las’Anod, the capital of the Sool region, between the Somaliland National Army and militias of the Dhulbahante clan, Puntland, and Al-Shabaab, has been characterized by increasingly opposing and unbridgeable narratives about what precipitated the fighting. While traditional leaders in Las’Anod who declared war claim they are defending their community from growing insecurity and fighting for self-determination, which is justified by a common desire to reconnect with Somalia, Somaliland accuses “terror groups” of starting the conflict.

After a protracted struggle against the dictatorship regime in Somalia, Somaliland regained its independence from the Union of Republic of Somalia in 1991. Las’Anod is located in the Sool region, on the eastern side of the Republic of Somaliland, which borders Puntland, a member of the federal government of Somalia. In July 1960, the British protectorate and Italian Somalia united to become the Republic of Somalia. Since claiming its independence in 1991, the Republic of Somaliland has developed a government with its own laws, a powerful military, a variety of law enforcement and security organizations, and all other necessary institutions.

After Garaad of Dhulbahante, Garaad Jama, proclaimed a war against Somaliland and his intention to secede and reconnect with the Federal Government of Somalia, fighting broke out on February 6. Other traditional leaders in the Somali region responded that Garaad Ali’s deliberate declaration of war in front of a crowd was immature for a traditional leader or for handling the situation in an appropriate manner. Since the beginning of the war, the Garaad’s declaration has resulted in the destruction of all basic life services, including hospitals and schools, and has created a chaotic situation in Las’Anod. Residents have been forced to flee their town and have destroyed their means of subsistence, which has put them in an impoverished and precarious situation..

According to Somaliland, which sees itself as the successor to the former British Somaliland Protectorate, the territory was once a part of the protectorate’s original borders. Due to kinship ties to the prominent Darood clans in the region, Puntland claims Sool.

African land borders were marked by colonial powers. In Africa, one tribe may live in various nations. For instance, in Ethiopia, Djibouti, and Eritrea are home to Anfar tribes. Aside from that, the demarcation of territory is based on land as colonizers drown rather than tribe lineage. Therefore, no nation can disregard the established colonial borders and assert that it divides its territory according to tribe in order to impede another African nation.

Borders have been a recurring cause of conflict and controversy on the African continent since the continent’s independence. Recognizing this fact, African Heads of State or Government issued Resolution AHG/Res. 16 (1) at the Cairo Summit in July 1964, announcing the preservation of existing borders at the moment of independence. As a result, the principle of border intangibility, applies within the framework of the Organization of African Unity. Las’Anod is now Somaliland’s territory in accordance with the African colonial borders, therefore Majartenia cannot claim it for tribal lineage or use it to split people along the border in an emotional tribal ego uprising. Similar to Somalilanders, Dhulbahante, Issa, and Gadabursi, who have sizable populations living in Ethiopian boundaries, cannot unilaterally claim Ethiopian territory out of tribal ego. International law supports observing, protecting, and implementing African Colonial borders.

A contentious and fiercely polarized struggle over the predominate narrative has evolved as fighting between Somaliland forces and various armed factions continues in Las’Anod. This parallel conflict, which is fought primarily on social media, involves participants from all over the world, including Diasporas, journalists, academics, and even competing US lobbying firms. This tangle of opposing discourses has a tendency to explain the causes of the conflict in wildly divergent and essentially in commensurable ways.

However, due to the fact that Somaliland lacks de jure recognition and is situated in a region with constant warfare, militant groups like Al-Shabaab and pirates who are not pleased with Somaliland’s peaceful resistance to them may seek to start a fire.

The assassination of the local elites who had been killing since 2009 after Somaliland’s military forces fought and drove Puntland out of Las’Anod may have been the work of Puntland, which was looking for a means to incite conflict between residents of Las’Anod and Somaliland.

The fact that everyone killed by the unidentified assailants was a member of the Somaliland system—including some government officials, police chiefs, and opposition groups—indicates that the claim that Somaliland was responsible for the killings is untrue.

However, a political crisis over postponed elections in 2022 highlighted the increasingly acrimonious internal rivalry among the Isaaq sub-clans for leadership of the state. Traditional leaders were arbitrarily detained, and five citizens were killed in clashes with security forces during anti-government demonstrations in Hargeisa in August 2022. These killings and the shooting of demonstrators in Las’Anod at the end of 2022, the government admitted and took responsibility.

Without a doubt, Garaads and some Dhulbahante figures are exploiting these tensions and inciting violence for their own political ends, but if they continue to sow chaos in the Sool region and the city of Las’Anod, there is an imminent danger that Al-Shabaab, which has agents spread throughout the Somali territories and thrives in unstable environments, will take advantage of the situation.

If outside meddling is avoided, Somaliland possesses the knowledge and resources necessary to handle internal conflicts, as well as the unresolved and frequently unacknowledged problems in Sool.

According to SIHA Network’s report, Most of the women and girls displaced by the Las’Anod conflict are living in precarious and dire situations; some are living in makeshift shelters in the open and or under trees despite the rain, wherein their basic needs are not being met. Even though it is regrettable that Garaads and other local leaders are preventing aid from reaching victims, both sides must abide by calls from international communities for “an immediate de-escalation of violence, the protection of civilians, unimpeded humanitarian access, and for tensions to be resolved peacefully through dialogue.”

Yousef Timacade is lawyer, legal analyst and commentator. He has a master’s degrees in law and executive management, and has been working with national and international non governmental organizations for the last ten years in the areas of program management, research, and human rights.